Correcting More Flawed Armchair Objections to GMOs

(original image credit to Chuck Lasker)

Loring has decided to reply to our initial exchange on Twitter. Sadly, he merely repeats the same false claims about GMOs, denies the consensus on GMO safety while insisting that he is not anti-GMO, and just calls opponents “aggressive” and “trolls”. Many of these claims were already addressed and debunked in the previous article Correcting Flawed Armchair Objections to GMOs, but let us debunk the remaining claims as well.

Loring starts his twitter screed by simply, without evidence, labelling his critics as “aggressive” and “trolls”. This is a fallacy known as poisoning the well, whereby claims are made about a target in order to discredit or mock him or her before the arguments have been evaluated. It is a feeble attempt to play to his base so that people will come into the discussion about the evidence with a biased frame already in place. This is to prevent them from questioning the arguments and claims being made, because, of course, you do not want to belong to the outside tribe and suffer the same verbal attacks. In fact, through his twitter screed, Loring makes several other fallacies, including insisting that science advocacy on GMOs is like being pro-gun. The implicit message Loring tries to send is that science advocates are evil people via a guilty by association fallacy. Of course, the comparison is flawed since the scientific consensus goes against the gun lobby, not supports it.

You actually can demonstrate safety

In this post about the scientific consensus, Loring insists that you cannot demonstrate safety, merely a lack of harm. This is not true for several reasons. First, genetic modification involves fewer, more precise, more well-known and more well-tested changes, genetic modification produce less risk than conventional breeding. Here is a helpful table:

| Traditional plant breeding | Production of GM crops | |

| What is the size of the genetic changes? | Genetic recombination causes hundreds to thousands of large genetic changes. | Adding or modifying one or a few genes qualifies as small genetic changes. |

| How precisely are the changes done? | Very low precision because breeders often rely on look at the phenotype. | Extremely high precision because scientists can use methods such as DNA sequencing and others. |

| How well-known are the genetic changes? | Unknown since you are only looking at the phenotype. | Highly characterized, both by virtue of the techniques involved and because of regulation requirements. |

| How long does it take? | Decades, unless you mutate seeds with chemicals or radiation (which still qualifies as traditional plant breeding by regulators). | Very fast. |

| When can they be released? | Often right when they are made. Little or no government regulation. | Typically after 10+ years of intense toxicological and ecological testing. |

This means that crossing any two plants produces changes in many more genes than just one or a few. Due to the way genetic recombination works, there is very little precision in conventional breeding. The genetic changes are also completely unknown as the breeder only looks at phenotype. But if you can accept traditional crossbreeding despite the fact that each crossing produces large, imprecise and unknown changes, then you should accept genetic modification.

Second, because GMOs are so heavily regulated, evidence of harm would refute the safety claim had they existed. Third, GMOs have been shown to be substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts. Fourth, the bulk of the scientific literature shows that GMOs are safe.

So from multiple lines of evidence, we know that GMOs are generally safe. Loring systematically and intentionally misinterprets this as to mean that whatever future GM applications that gets developed must be safe and if it is not, one cannot say there is a consensus on GMO safety. This is, of course, ridiculous. He would never use that argument to deny the consensus on vaccine safety or the scientific consensus on global warming. Imagine if someone were to wrongly claim that we cannot say that vaccines are generally safe because there might be a vaccine developed in 30 years that is not safe. Imagine if someone were to wrongly claim that we could not say there is a consensus on global warming because we might discover some currently unknown natural forcing in the future. Loring would rightly reject those anti-consensus arguments as evidence-free, confused and downright batshit. He should therefore do the same with his anti-consensus arguments with respect to GMOs.

GMOs is just an extension of other breeding methods

(image credit: Biochica)

Since we saw about that GMOs merely involves making genetic modifications that are fewer in number, fewer in size, more precise and more well-known, it is reasonable to view genetic modification as an extension of artificial selection. Loring disagrees and makes the following claim:

One important difference is that in the field, domestication and artificial selection occur in an interplay with wild biodiversity.

This isn’t actually true. Modern industrial agriculture does not happen in an interplay with wild biodiversity. This is because it relies on removing weeds and other pests and is done in an industrial setting designed to maximize efficiency and productivity. Indeed, one of the major criticisms of the Green Revolution was that it harmed biodiversity (due to e. g. monocropping as well as reliance on pesticides and fertilizers).

Loring is suffering a bias called rosy retrospection. He dreams back to simpler times where artificial selection was done slowly and in harmony with nature. The problem, of course, that he is dreaming of a past that never was. The artificial selection done during the Green Revolution was not an interplay with wild biodiversity. In fact, one of the reasons why the Green Revolution was so successful and saved millions of people from starvation was that it rejected the interplay with wild biodiversity by optimizing crop strains, used pesticides to get rid of pests that harmed yield and used fertilizers to boost agricultural output.

Perhaps Loring want to go back even further to a time before the Green Revolution? Then he would have to cut global productivity to less than one third, effectively making him worse than the Marvel villain Thanos. How many people will die in Loring’s Brave New World? Of course, in a world with just one third of the global agricultural output, the losers will be the poorest people in the world as rich countries can leverage their wealth to get food.

This is one of the problems with anti-GMO activists like Loring. They are armchair researchers who has never done any real lab or field work in the natural sciences and therefore does not have a good grasp of the areas. They are also armchair farmers who have never done any real work on a farm. This is especially embarrassing when they insist that farmers want to save seeds. They don’t. Farmers want high-yielding homozygous seeds, not weaker hybrid seeds.

They have a rosy and distorted view of a past that never really was. Having opinions about biotech and farmers are great, having informed and evidence-based opinions is better.

In the lab, however, genetic modification benefits from none of these external inputs, and this has ramifications for the question of whether or not GMOs are ecologically “safe”.

Whether something is done in a lab or not is not an argument specific to GMOs. Seedless watermelons and a whole host of other traditional crops are made in labs. Virtually all crops made by mutational or radiation breeding is done in one kind of lab or another.

Of course genetic modification benefits form these external inputs. This is because the original crop being modified comes from that ecological context or the modified plant is then crossed into existing, locally adapted variants via traditional crossbreeding. The ecological safety of GMOs is shown in long-term ecological studies.

Again, this highlights the stunning ignorance of Loring when it comes to how lab-based methods work and how actual farming works.

Domesticates are generally poor at reproducing without human intervention, but pollen drift is a legitimate issue (a similar issue can be raised for genetically modified salmon). We simply cannot know ahead of time what sorts of ecological consequences different GMOs may have in different ecosystems.

Another basic scientific error. This is because many GM crops are obligate self-pollinators. This means that they cannot physically pollinate other plants, only themselves. Had Loring had a basic understanding of how plant biology works, he would have known this. But since Loring lacks any education and research experiences in the natural sciences, this information has escaped him.

Loring also did not bother to read his own reference:

Corn pollen is among the largest particles found in the air. Although it is readily dispersed by wind and gravity, it drifts to the earth quickly (about 1 foot/second) and normally travels relatively short distances compared to the pollen produced by other members of the grass family. Pollen may remain viable from a few hours to several days. Pollen can survive up to nine days when stored in refrigerated conditions. However, under ambient field conditions, pollen is viable for only 1 to 2 hours. High temperatures and low humidity reduce viability

It further notes the following about distance:

However, most of a corn field’s pollen is deposited within a short distance of the field. Past studies have shown that at a distance of 200 feet from a source of pollen, the concentration of pollen averaged only 1% compared with the pollen samples collected about 3 feet from the pollen source (Burris, 2002). The number of outcrosses is reduced in half at a distance of 12 feet from a pollen source, and at a distance of 40 to 50 feet, the number of outcrosses is reduced by 99%

Thus, Loring’s own reference shows that pollen spread from corn is not really an issue.

There are even more arguments for why pollen spread is not a legitimate issue: genetic modifications done to chloroplasts do not spread by pollen since those are inherited maternally. Genes that produce beneficial traits in the field is of little selective benefit in the wild. For instance, producing more vitamin A precursors or being resistant to glyphosate is not a selective benefit to rice growing in the wild.

This is another thing about anti-GMO activists like Loring. They do not read or understand their own references.

However, what we can infer from niche theory is that the risks of novel, disruptive species emerging would be significantly lower for new varieties developed in situ as opposed to those developed in a lab.

No, that is not a legitimate argument since crossbreeding involves many more and larger genetic changes that are less precise and less well-known than genetic modification. Furthermore, genetic modification does not create a new plant out of scratch, but using those existing plants that are locally adapted or gets crossed into them before. Again, Loring lacks sufficient knowledge about plant biotechnology and farming. This is even more apparent in the following set of claims:

There are numerous other possible environmental concerns, regarding the use of pesticides, the development of herb-resistent weeds, and health impacts of plant and animal exposure to Round-up and neonicotinoids

Pesticides are not GMOs. Many studies show that GMOs reduce the use of pesticides by as much as 37-41% depending on crop and location. In particular, the Bt system has reduced reliance on harmful insecticides. This means that farm workers spend much less time spraying fields with insecticides and reduce the risk of harming themselves and the environment.

It also replaces much more dangerous pesticides with less dangerous pesticides like glyphosate. It is not just the amount of active ingredient that is important, but what kind of pesticide is used. Generally speaking, safer pesticides are better than more dangerous pesticides and narrow spectrum pesticides are better than broad spectrum pesticides. This pedagogic graph (p. 28) that illustrates the replacement of more dangerous pesticides:

Finally, in some cases, it can even totally eliminate the use of pesticides by making the plant naturally resistant to the pathogen. This is how genetic modification saved the Hawaii papaya from being completely decimated. A gene encoding the complimentary sequence of a coat protein of the papaya ringspot virus (PRSV) was put into the papaya under a pathogen-inducible promoter. Thus, when the virus infected the papaya, the gene was transcribed, produced the complementary RNA to the virus and triggered the plants own defense system called RNA interference against the virus and resisted the infection.

Anyone who brings up pesticides as a downside of GM crops has literally no idea what he is talking about. Growing GM crops reduces pesticide use, eliminates it all together or replaces it with less harmful pesticides.

The issue of herbicide resistance weeds (not herb-resistant weeds as Loring writes) is another issue that is not related to genetic modification as a particular breeding method. Weeds that grow resistant to herbicides is a feature of herbicide use, not a feature of using genetic modification. Herbicide resistance develops in conventional and organic agriculture as well, and farmers solve it by switching herbicides. For those that are unaware, organic farming also uses pesticides, but they are organic, rather than synthetic. This includes copper sulfate, boric acid, pyrethrins and many others.

Loring takes it to even more absurd levels when he tries to bring up “animal exposure to neonicotinoids”, when neonicotinoids is a pesticide use in conventional agriculture, not on GM crops. In fact, there are no GM applications that relies on neonicotinoids at all. In essence, Loring is just fearmongering about pesticides in an effort to scare his followers into rejecting biotech crops using a guilt by association to pesticides. It is both intellectually dishonest and scientifically ignorant.

Bottom line: if you are against pesticides, you should be in favor of GMOs.

If you deny the consensus on GMOs, you are anti-GMO

Loring continues with his insistence that he is not anti-GMO, yet continue to deny the consensus on GMOs. He just digs himself further and further down into inconsistencies and contradictions. This time he becomes even more equivocal. Watch the following attempt to create a smokescreen:

This is not how you do science.

The consensus position is based on the independent convergence of evidence from hundred and hundreds of different studies. It is robust. That means it is better than the results from one or a couple of studies. That is literally what scientific consensus means: a consensus position is a position that is supported the bulk of the scientific evidence. Read more about the meaning of scientific consensus in What is Scientific Consensus and Why Should You Care?.

People who reject the scientific consensus on issues like climate, vaccines or GMOs often want to rely on cherry-picked single studies rather than to prioritize the scientific consensus. The belief is that if they can find one or a few studies that seem to point somewhere else, then can demand that those papers be given the same weight as the scientific consensus. But this is just not true. The weight of the scientific consensus completely crushes the merits of single studies.

Objecting to a scientific consensus position by citing a few cherry-picked papers that seems to support your position is not intellectually honest and it is not a scientific way to work with the literature.

Imagine Loring arguing against climate deniers on Twitter. He brings up the easily verifiable fact that there is a scientific consensus on global warming. The crushing majority of scientific papers all converge on the conclusion of global warming. In fact, the consensus is so strong that multiple consensus studies show a consensus. We know global warming is real and we know that humans play a decisive role in it.

Imagine that the climate denier then goes on to oppose this consensus by citing a couple of the papers that rejects the consensus and demands that Loring give them equal weight. Loring would immediately and rightly point out that this is not how science works. You do not get to cherry-pick a couple of papers that reject the climate consensus and pretend that you have not disproved the consensus or even come up with a relevant challenge.

If only Loring could see that his behavior when it comes to the consensus on GMOs is just as intellectually bankrupt as the approach climate deniers take to the consensus on global warming. This is not a guilty by association. I have clearly demonstrated considerable similarities in the general argument made.

So the bottom line is that Loring partially accepts the scientific consensus, but cherry-picks papers that rejects it in a pseudoscientific way and pretends that they have a comparable weight. They do not. This issue could be left at that, but let us go through and debunk even those cherry-picked papers.

Cherry-picked paper #1: Krimsky (2015)

Note that the National Academies report Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects that I cited is from 2016. The first cherry-picked paper is from one year earlier (2015).

Let that sink in.

In an effort to challenge the scientific consensus on GMOs, Loring cites (with a straight face) a paper that was written before the National Academies consensus report was even published. Whether intentionally or by mistake, this is shockingly intellectually dishonest. You do not get to pretend that time travel is possible. The later document that is much more robust outweighs an earlier, single study. That is the entire point with scientific consensus: to look at where the bulk of the published scientific evidence points to.

Again, I could leave it at that, but let us dig deep into the paper and expose it. First, we should note that it is a paper about the health effects of GM crops and not the broader societal questions that Loring often wants to focus on.

Who is the author? Why should we consider him a legitimate expert on the the health effects of GMOs? On this department website, he calls himself a “Lenore Stern Professor of Humanities & Social Sciences” or “Professor of Urban & Environmental Policy & Planning”. Now, does this have anything to do with plant biotechnology? No. Does it have anything to do with medicine? No. In other words, Krimsky lacks the relevant scientific background for us to consider him a genuine expert on the topic. In other words, he is a fake expert. This does not mean he is wrong on any particular claim (that would be a fallacy). But it does mean that we should not consider him an expert on the topic. He is writing about something he finds interesting and worthwhile, but he is not a relevant expert.

The use of fake experts to spread fear, uncertainty and doubt about mainstream science is exceptionally common. Oil companies and various other anti-environment think tanks trout out physicists who denies that smoking causes lung cancer or denies that global warming is real and that humans are harming the environment. To learn more on how to spot a fake expert, check out the fake experts entry in the science denialist tactic series.

Let us move onto the paper itself.

It is divided into three sections. The first section is claimed to be a systematic review of animal feeding experiments and positions taken by scientific and medical organizations on the health effects of GM crops. Second, he discusses two anti-GMO papers and the response to them by the scientific community. Third and finally, he discusses some of his conclusions about the consensus.

Remember, Loring has in a previous blog post clearly stated that he accepts that long-term animal feeding trials show that GMOs are safe:

To my knowledge, there is indeed no evidence that the GMO foods currently in production are unsafe. What’s more, several studies, including one of billions of livestock fed GM, feed have indeed shown no adverse effects.

Yet the paper his cites now rejects this. Thus, Loring uses a reference that contradicts his own position. Clearly, Loring has not read the paper he is referencing, or at least not understood it. Let us see what Loring claims:

The method of the Krimsky paper boils down to looking for systematic reviews in the PubMed and Web of Science databases between a short, arbitrary set of years (2008 and 2014) and found eight such reviews. Then he mere tabulated the results of those systematic reviews without carrying out any kind of deeper analyses of the papers for methodological quality. A quick glance at checklists for how to carry out systematic reviews, such as AMSTAR and PRISMA, shows that the Krimsky paper fails most of the criteria. It is thus an exceptionally low quality systematic review. In fact, it is not even systematic as he does not mention what search terms he used. It is, in fact, a narrative review poisoned by the anti-GMO biases of the author, who is not a legitimate expert in the field.

In other words, the flawed claim that “One cannot read these systematic reviews and conclude that the science on health effects of GMOs has been resolved within the scientific community” is based on a flawed narrative and completely uncritical review of eight papers. The scientific consensus outlined in Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects is based on a much larger set of research papers and was carried out more recently than that of Krimsky. This consensus document was also worked on my people who are genuinely experts in the area, unlike Krimsky.

The Krimsky paper then continues and actively cherry-picks papers that goes against the consensus position. This, of course, is not scientific. Krimsky is not allowed to arbitrarily focus on papers that conforms to his belief that GMOs are dangerous to health or that there is no consensus on GMOs. Krimsky spends the rest of this section focusing on two papers he finds particularly intriguing:

Ewen, S. W. B., and A. Pusztai. (1999). Effects of Diets Containing Genetically Modified Potatoes Expressing Galanthus nivalis Lectin on Rat Small Intestine. Lancet 354 (9187). 1353-54.

Séralini, G.-E., E. Clair, R. Mesnage, Steeve Gress, Nicolas Defarge, Manuela Malatesta, Didier Hennequin, and Joe¨l Spiroux de Vendoˆmois. 2012. Long Term

Toxicity of a Roundup Herbicide and a Roundup-tolerant Genetically Modified Maize. Food and Chemical Toxicology 50:4221-31.

A review (cache) by the Royal Society showed that the Pusztai paper had multiple methodological flaws that undermine its conclusions. The review found that:

In summary, the data presented to the reviewers and Working Group are inadequate for the following reasons:

• poor experimental design, possibly exacerbated by lack of ‘blind’ measurements resulting

in unintentionally biased results;

• uncertainty about the differences in chemical composition between strains of non-GM

and GM potatoes;

• possible dietary differences due to non-systematic dietary enrichment to meet Home

Office and other requirements;

• the small sample numbers used in experiments testing several diets (all of which were

non-standard diets for the animals used) and which resulted in multiple comparisons;

• application of inappropriate statistical techniques in the analysis of results;

• lack of consistency of findings within and between experiments.The uncertainty and ambiguity of the data urge great caution in the interpretation of the results presented. A much improved experimental design, with stringent controls, would have been needed if the claims made for the study were to be convincing. Even if the results of the particular study had supported the claims that have been made for them, it would have been unwise to use them for making statements about the safety or otherwise of all GM foods.

A later EFSA review on animal feeding trials show that there is at least a 100 times safety margin between the dose given to animals with human intake and that there is no practically significant differences between the experimental and control groups. In addition, as Loring himself pointed out, we know from feeding billions of on animals GMOs that they are safe to eat.

Sadly for Krimsky and Loring, the Séralini paper was retracted due to multiple overt methodological errors, including using rat variants that spontaneously developed cancer, using inappropriate statistical analysis, including too few rats in each group to capitalize on chance correlations, there was no dose-response effect and crucial data on food and growth was missing. A 2015 re-analysis of the Séralini data found no negative effects, concluding that Séralini had not controlled for multiple comparisons. A trivial error in statistics that any competent researcher should have carried out.

In sum, the Krimsky paper does not refute the scientific consensus. It is a biased and uncritical narrative review of only 8 papers published within a few years. It puts extreme weight on papers that have extreme levels of methodological errors and even states his support for papers that are so bad they had to be retracted.

Loring continues to deny the scientific consensus on GMOs

Remember, a scientific consensus on an issue X (safety of vaccines, existence of global warming etc.) is the statement that the crushing majority of the published scientific research shows X. It is a descriptive statement. It is not an inference. It is a conclusion based on evidence. It is not a statement about everything that could possibly happen in the future. It is a descriptive conclusion based on the bulk of the published scientific research on the subject.

At this point, Loring is getting pretty desperate. He has to find some way to deny or reject the scientific consensus on GMOs. How does he do this? He completely butchers what scientific consensus means, apparently thinking that it talks about currently undiscovered future products or findings and that consensus requires zero risk:

A scientific consensus is a descriptive statement that the bulk of the published scientific evidence independently converge on the same general conclusion. For instance, that vaccines work, that global warming is real or that GMOs are safe. This does not require that all studies every published support the scientific consensus. It does not require that all research questions in the areas has been solved. It does not require any assumptions about future research discoveries and it certainly has nothing to do whatsoever with regulatory questions. These are all distractions people make to avoid having to accept the existence of a scientific consensus.

Next year, we might discover an unknown natural climate forcing that forces us to slightly tweak certain climate estimates. We might discover a vaccine that turns out to be disappointingly ineffective or have a less beneficial side effect profile. In other words, these are possibilities that exists everywhere. New things might be discovered, whether scientific findings or new technological development, that changes how we view the world.

This, however, has nothing whatsoever to do with whether or not there exists a scientific consensus in the research literature. Loring would almost certainly reject his objection had it been levered against the scientific consensus on vaccines or climate. Thus, he should reject it when it is applied to GMOs as well.

Furthermore, the existence of a scientific consensus does not demand “zero risk”. In fact, there are very rare risks with vaccines, including 1 in 1 000 000 risk for a severe allergic reaction, risks of fever and other side effects. However, we know that benefits outweigh the risks. There are risks with climate mitigations, but the benefits clearly outweighs that risk. Loring wrongly assumes that a scientific consensus on safety requires zero risk. This is simply not true, because zero risk is not possible.

The fact that we evaluate products based on a case-by-case basis or the existence of regulatory systems is also not an argument against the existence of a scientific consensus, because vaccines are regulated and evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Imagine if someone had made the argument that regulating and testing vaccines meant that there was no consensus on vaccine safety or efficacy! Loring would have been furious. In reality, the existence of the consensus on vaccine or GMO safety is precisely because there are regulations and things are tested and evaluated by a case-by-case basis. Thus, it is not an argument against the scientific consensus, not a necessary prerequisite for it.

GMO labelling is a deceptive warning label for safe things

Loring reiterates his support for GMO labelling:

To this, we can respond with the following illustration:

There are many problems with GMO labelling:

(1) It increases misconceptions about the health effects of GM foods.

As the illustrating above, it will make people think “why does it need a warning if it is so safe?”. We already know that consumers are very ignorant about food. For instance, 80% of consumers want to label food that contains DNA (virtually all food contain DNA). The anti-GMO movement is also very widespread and it is based on a host of misconceptions about GMOs.

(2) It limits consumer options.

Companies do not want a flawed warning label on their foods, so they will largely abandon GM products and ingredients. This will limit the amount of options available to consumers.

(3) It will increase food cost for the consumer.

GM crops and ingredients are cheaper. When companies remove GM products and ingredients, they will have to work with more expensive products and ingredients. This will increase food costs by several hundred dollars per year.

z

(4) It will increase administrative work for farmers.

GMO labelling will require farmers to spend more of their time on administrative work. Not just for complying with regulations but also ensure that their products could stand up to lawsuits claiming that their products are not really non-GMO.

(5) It will increase stigma against beneficial technologies.

As if have seen the anti-GMO movement demonizes beneficial biotech methods and products, even though they reduce pesticide use, increase yield and increase farmer profits.

Food labels should give people insight into the contents of their food, not the specific breeding method that has been used to make it. For instance, there are no labels on food indicating that they were the result of artificial selection, hybridization, mutational or radiation breeding. Anti-GMO proponents know that labelling will further harm the scientific literacy of the public. After all, why label something if it is not dangerous? After all, labels confer information about salt content, allergens etc. that are useful for people to avoid if they need to.

Again, the fact that there exists a scientific consensus on GMOs does not mean that “all GMOs will always be safe based on existing examples”. In fact, no one has every claimed this in this discussion. The analogy to guns is also flawed. This is because “muskets and Derringers” are dangerous. They kill people. They have been used in wars that have killed literally millions of people. Besides being in total error, Loring has also provided an example against his own argument. The fact that we know that muskets are dangerous as as scientific fact also allows us to conclude that weapons that shoot more and faster bullets will be even more dangerous. That is a perfectly valid inference.

Cherry-picked paper #2: Hilbeck et al. (2015)

The second cherry-picked paper Loring relies on to reject the scientific consensus on GMOs is “No scientific consensus on GMO safety” published by Angelika Hilbeck and colleagues in 2015 in the journal Environmental Sciences Europe.

Hilbeck is an entomologist who has never done any research on plant biotechnology. Another co-author is Vandana Shiva, a philosopher who infamously compared farmers to rapists:

To think that this paper is a scientific and dispassionate analysis of the evidence beggars belief.

The same problem applies here: it is a paper published before the National Academies report, so it can obviously not be a criticism of it. It is a single paper that does not take into account the bulk of the scientific evidence in the research literature. Its dismissal of scientific consensus relies on uncritically pointing to the mere existence of five papers (including the now retracted Séralini paper) that appears to be inconsistent with the broader research literature.

Finally, this paper does not bring up any new evidence that has not been considered by the National Academies consensus report.

The anti-GMO movement has a social justice problem

In our exchange, I cited the article The Anti-GMO Movement Has A Social Justice Problem. Here is how Loring responded.

This is the shortsighted Your anti GMO argument is: “We already have enough food to feed the world”.

First, it assumes that poor countries should rely on the leftovers of rich countries instead of developing their own robust and sustainable agricultural systems. This is a terrible idea and requires that poorer countries are stuck in a subservient food relationship with the U. S. and Europe. As the article points out, many anti-GMO activists do not want to see such a reliance on seed companies, so why should such a reliance be good when it is based on governments?

Second, we may produce enough food right now, but in the upcoming decades we will suffer the effects of global warming, loss of arable land and a population that will grow by a few billions. Then we will not have enough food to feed the world. What does Loring suggest instead of using modern technology? That we go to organic farming, which decreases yields by 34% when organic and conventional farming is most comparable? Who will suffer from such a yield loss? Not rich countries that have the money to buy the food at a much higher cost, but poor people that cannot.

Anti-GMO activists like Loring almost never face up to these challenges. This is why the fake concern for social justice in the anti-GMO movement is so frustrating.

Loring also conveniently ignore the fact that studies show that genetically modified crops increase yield by 22% on average.

The fact that there is a natural range in yield increases that depend on what you are growing, where you are growing it and under what circumstances is not an argument. This is because that is a constant feature of agriculture. You have to look at the average and the evidence is clear: GMOs increase yield. The natural range for agriculture can be easily improved over time by continuing with practices that work and reducing practices that do not. Loring is also limiting himself to the U. S. where yield increases will be less since they already have a very optimized agricultural system compared with many other countries.

Loring claims that smallholders are often losers. This just is not the case. 60% of profit increases go to . Even the National Academies report (that he claims to have read) show that smallholders benefit from GMOs:

GE maize, cotton, and soybean have provided economic benefits to some smallscale adopters of these crops in the early years of adoption. However, sustained gains will typically—but not necessarily—be expected in those situations in which farmers also had institutional support, such as access to credit, affordable inputs, extension services, and markets. Institutional factors potentially curtail economic benefits to small-scale farmers.

VR papaya is an example of a GE crop that is conducive to adoption by small-scale farmers because it addresses an agronomic problem but does not require concomitant purchase of such inputs as pesticides. Other technologies currently in the R&D pipeline—such as insect, virus and fungus resistance and drought tolerance—are potential candidates to accomplish the same outcome especially if deployed in crops of interest to developing countries.

Investments in GE crop R&D may be just one potential strategy to solve agricultural production and food security problems because yield can be enhanced and stabilized by improving germplasm, environmental conditions, management practices, and socioeconomic and physical infrastructure. Policy-makers should determine the most costeffective ways to distribute resources among those categories to improve production.

Again, Loring does not seem to read or understand his own references.

The fact that there are other important things do to besides growing GMOs (access to credit) does not disprove the fact that GMOs are beneficial for smallholders. It is also suspect that Loring wants to encourage farmers to go into debt.

No one is trying to claim that GMOs will compensate for the downsides of industrial agriculture. What is being claimed is that there is a consensus on the safety of GMOs and that GMOs benefit farmers in terms of yield, reduced pesticide usage and farmer profits and that this also happens for small farms.

But what about biological diversity?

Most of the remaining tweets by Loring focus on issues he dislikes about industrial agriculture which has nothing to do with the particular breeding methods used. Indeed, had he actually read the National Academies report, he would have seen that growing GMOs boost biodiversity.

GMOs increase insect biodiversity.

Planting of Bt varieties of crops tends to result in higher insect biodiversity than planting of similar varieties without the Bt trait that are treated with synthetic insecticides

This is because the Bt trait in plants is highly specific for a particular kind of pest and reduces the need for broad-spectrum insecticides that harms many non-target insects.

In the United States, farmers’ fields with glyphosate-resistant GE crops sprayed with glyphosate have similar or more weed biodiversity than fields with non-GE crop varieties.

Again, this is because glyphosate is now used instead of much more dangerous herbicides and thus does not have as negative effects on biodiversity. Even the observed reduction in crop diversity cannot even be attributed to GMOs, but may be because of changes in prices:

Since 1987, there has been a decrease in diversity of crops grown in the United States—particularly in the Midwest—and a decrease in frequency of rotation of crops. Studies could not be found that tested for a cause–effect relationship between GE crops and this pattern. Changes in commodity prices might also be responsible for this pattern.

Indeed, there is not even an historical correlation:

Although the number of available crop varieties declined in the 20th century, there is evidence that genetic diversity among major crop varieties has not declined in the late 20th and early 21st centuries since the introduction and widespread adoption of GE crops in some countries.

Loring does not tell his followers any of this, but goes on to demonize GM crops as if they were somehow harming biodiversity.

Organic farming uses pesticides

Loring cites a Nature Plants review paper called Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century on organic farming and claims that “the myriad other social and ecological outcomes suffer in comparison to organic agriculture”.

However, a careful reading of the paper shows that they intentionally left out the environmental impacts of organic pesticides used in organic agriculture and only looked at synthetic pesticides:

Whereas organic systems yield less food, organic foods have significantly less to no synthetic pesticide residues compared with conventionally produced foods. Studies have also found that children who eat conventionally produced foods have significantly higher levels of organophosphate pesticide metabolites in their urine than children who eat organically produced foods. In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics reported that an organic diet reduces children’s exposure to pesticides, and provided resources for parents seeking guidance on which foods tend to have the high- est pesticide residues. Although these data show that organic food may present some clear advantages when it comes to synthetic pesticide residues, the human health impacts of pesticide exposure from food are not clear, and organically certified pesticides need to be better identified and taken into account.

Again, Loring does not explain this to his followers. Presumably he has not read and understood the paper.

Farmers do not want to save seeds

Loring keeps bringing up that farmers want to save seeds. This is, of course, generally inaccurate. Farmers do not generally save seeds for the next round of crops and do not really want to either. This is something that Loring might have known if he had talked to actual farmers instead of being an armchair philosopher telling farmers what they should do even though he has no experience with farming himself.

The reason why saving seeds is largely an outdated practice (and has not been common since the 1930s) is because farmers use high-yield hybrids with beneficial traits. Due to the basic facts behind plant reproduction, man seeds in the next generation of will not produce beneficial trait. For the farmer, the best outcome comes from buying and planting new seeds. There are other factors, such as seed size uniformity, less time and money spent on seed cleaning, that also explain why seed saving is an outdated practice.

The fact that anti-GMO activists keep talking about a farming practice that has not really been a thing for 90 years show how out of the loop they are when it comes to farming.

Patents have nothing to do with GMOs

Predictably, Loring turns to a wide range of arguments against GMOs that have nothing to do with GMOs, such as patents. If you dislike patents, that means you dislike certain legislation related to intellectual property rights. It has nothing to do with a particular breeding method. In fact, both conventional and organic farming involve intellectual property rights, including Plant breeders’ rights.

Insect refuges are not “conventional farming”

Loring again displays his shocking ignorance of GM applications by claiming that insect refuges support conventional breeding.

This is not how insect refuges work. It goal is not to grow conventional and GM crops together so that you can harvest those conventional crops. They are designed to be eaten by insects that are homozygous for the susceptible gene variant. Keeping them alive means that a smaller proportion of the breeding insect population will be homozygous for the resistant gene variant (and be resistant to the effects of the Bt trait).

It has no relevance whatsoever if those crops are bred using a certain method or not, just that they do not contain the Bt trait. They can be bred via artificial selection, hybridization, organic methods or whatever. It is not support for conventional breeding as such. It is a method that allows farmers to mitigate and reduce the development of Bt resistance. The other common method is including multiple Bt variants, so insects that are resistant to one of them will be susceptible to the others and prevent the development and spread of resistance.

The plants without the Bt trait is typically only a small proportion of the entire field and the location is crucial.

Outdated references does matter

Loring insists that there is a no problem whatsoever with citing outdated reference:

Scientific research progresses over time. Relying on very old publications is problematic as newer research can contradict or even overturn it. Just consider medicine. Would Loring want to be treated by methods developed and tested in the 1990s, or the 2010s?

In the area of biotechnology, it is important to avoid relying on very old papers that are often without empirical data. This is because later scientific research has often tested the claims in those older articles and sometimes found them to be wrong.

So yes, the age of a publication absolutely matter for its veracity. Excessive reliance on old papers show that the person is not familiar with modern biotechnology or their research findings.

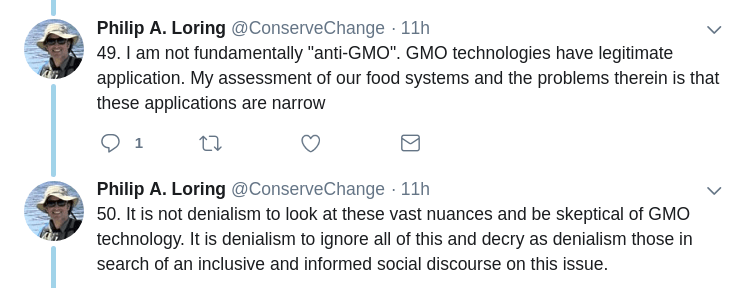

Yes, Loring is fundamentally anti-GMO

Loring finishes off by insisting that he is not anti-GMO. Despite having spent the previous 48 tweets rejecting the scientific consensus on GMOs and promoting classic anti-GMO tropes that have been debunked over and over again.

Loring just denies that he is anti-GMO and calls people who question him denialism. This is little different from the childish “I know you are, but what I am?” line of argument and cannot be taken seriously.

Look, Loring can talk about nuances and details until the cows come home, but it has nothing to do with the scientific consensus on GMOs. The vast majority of his objections are to industrial agriculture (patents, biodiversity etc.) and not about a specific breeding method (genetic modification). Throughout his tweet screed, he made several personal attacks, accused others of being trolls or plagued by confirmation bias when he obviously himself suffer from that bias.

When Loring denies and obfuscates the scientific consensus on GMOs, tries to cite individual papers that are older than the consensus report, refuses to read his own references, relies on outdated references that are over two decades old and just regurgitates the same old debunked nonsense over and over, it is denialism. Plain and simple.